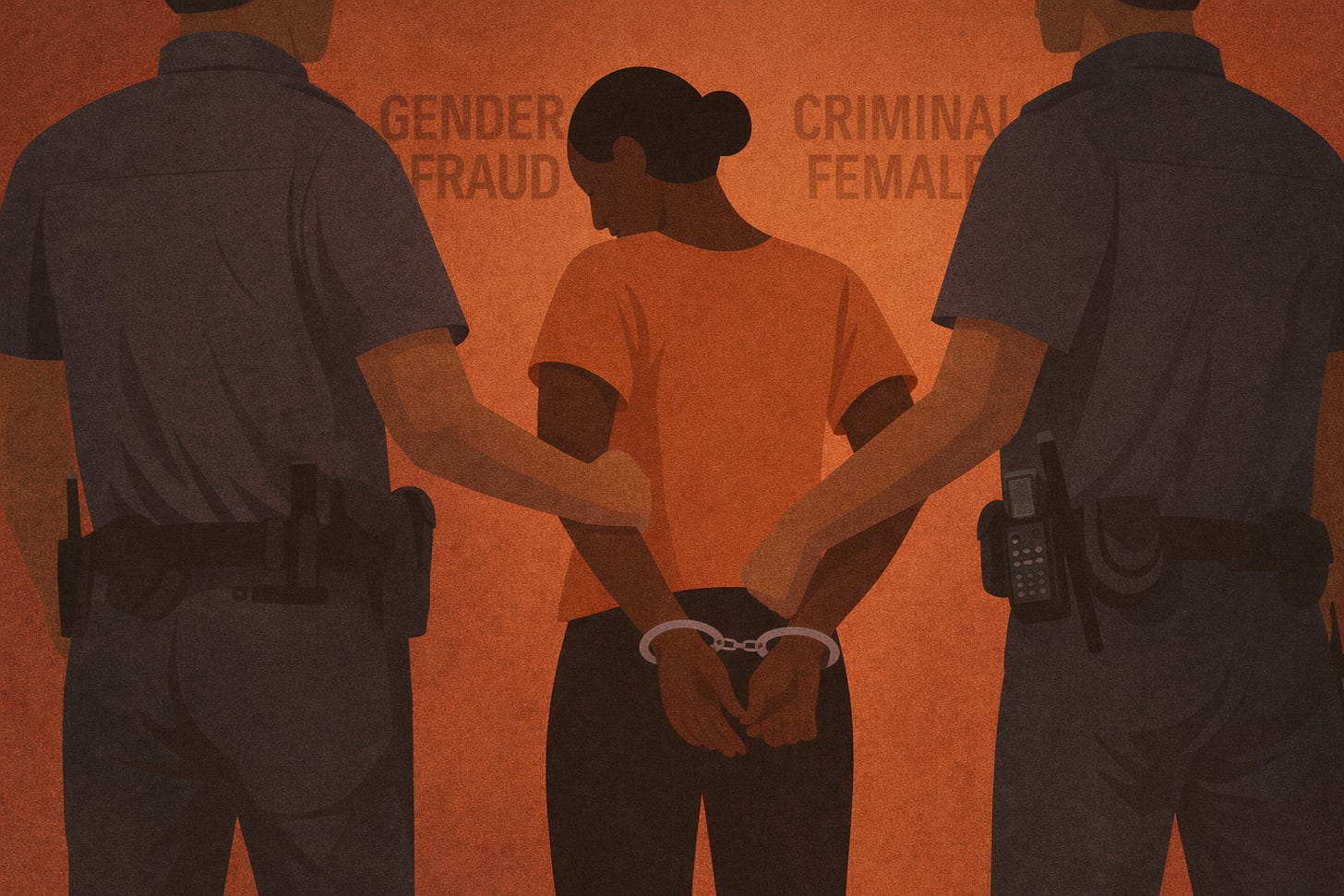

✍🏾In Her Words: Gender Fraud: When Patriarchy Criminalizes Female Autonomy

Guest Contribution by Jocelyn Crawley

The Peachy Perspective occasionally features guest posts from Southern radical feminists whose voices sharpen our collective fight for women’s liberation. In this In Her Words contribution, Jocelyn Crawley offers a radical feminist reading of Peg Tittle’s Gender Fraud, showing how androcentric ideology operates through punishment, psychiatric control, and the denial of female subjectivity.

Male supremacy is a malicious, malevolent sentient entity that thrives on ensuring that institutions and individuals conform to its insidious ideologies, one of which is that women are not fully human and can therefore be reduced to objects for the purpose of exploitative oppression; radical feminist Peg Tittle knows this and makes unveiling the ugly awry axiological framework of androcentrism an integral element of her important book Gender Fraud. In this text, Tittle predicates her analysis of male domination on a dystopic world in which parochial, patriarchal understandings of gender dictate that women abandon actions and attitudes that connote individuality and autonomy while embracing epistemological and ontological frameworks which promote deindividuation, superficiality, and preoccupation with the somatic dimensions of the self. The promotion of these aspects of normative femininity–all of which are predicated on the organization of a reality in which women are subordinated to men–contributes to the maintenance of the logics of sexist domination by ensuring that women do not utilize their minds in ways that challenge male power and female dependence on men.

Near the onset of the narrative, the reader learns that the protagonist–Kat Jones–has been arrested for Fraudulent Identity. Apprehended while running, the officers stop her and explain that she is under arrest for Gender Fraud. In elaborating on the charge, one of them explains that “You’re presenting as male, when, in fact, you’re female. That’s fraud. And a criminal offence” (6). In explicating what constitutes Gender Fraud, the officer asks if she disputes the facts of the case, which include that she is

wearing men’s clothing, that you are not wearing make-up, that your hair is short and undone, that you are not wearing any jewelry, that you are unmarried, that you do not have any children, that you have had your breasts removed [due to a cancer concern], that you have had your reproductive capacity nullified via tubal cauterization, and that you have pursued an advanced academic degree?” (11-12).

In reflecting on the officer’s assessments, Kat Jones begins thinking about who may have reported her. Inwardly and introspectively, Jones enumerates several men who, in living in the same neighborhood as her, have embodied various forms of toxic masculinity. Chuck, she remembers, had called her a “cunt” (6) after she left a printout in their mailbox explaining that the leaves they burned created toxicity in the air. Mike, she recalls, had called her a “bitch” and kicked her dog, Tassi, after she called the Ministry to determine whether there were any laws against his practice of cutting trees down along the shoreline (6, 7). As the list of toxic men continues, the reader grasps that the writer is setting the stage to create awareness of how the male supremacist climate in which Kat Jones lives is conducive to the production and proliferation of sexist laws which result in the dehumanization and objectification of women.

As the fictional novel unfolds, the specificity of the degrading oppression that Jones experiences becomes evident. The penalty for the crime of committing gender fraud is relocation to a psychiatric facility, and, upon arrival, the reader becomes acclimated to Jones’s inundation in the realm of androcentric thought and praxis. The counselor assigned to Jones informs her that she will help the imprisoned woman “adjust” (15), with this term operating as a euphemism for the sadistic process of reducing Jones to a slave-woman. Picking up on this reality quickly, Jones notes that the counselor’s disposition and mode of expression is characterized by a “permanent cheer” (15) which is ostensibly an integral, inalienable element of being a woman. In reading this component of the text, the reader may be reminded of Marilyn Frye’s assessments regarding how, under the system of male domination, women are expected to maintain dispositions which include smiles for the purpose of conveying their appreciation of patriarchy and willingness to acquiesce the males who have more power than them within its hierarchical, binary-based structure. The annihilation of independence and identity, an integral element of normative constructs of humanness, transpires as Jones grasps how, rather than being permitted to operate as organically thinking and multifariously feeling sentient entities, female people are required to express a limited range of emotions; moreover, these emotions must be contiguous and continuous with obedience to the system of male domination.

As the text continues to unfold, the reality of the psychiatric facility operating as a training ground for female subordination and objectification becomes increasingly salient. Shortly after entering the facility, Jones’s clothes are replaced with the prototypically parochial and patriarchal garb prescribed for women: dresses. In receiving the dress she is supposed to wear while in the center, the counselor asks her if the size is right. Jones responds that she doesn’t know and subsequently recalls a former era during which, while teaching in college, the discourse of her female students functioned as evidence of their immersion in the aspect of male supremacist ideology which involves women conforming to normative (dehumanizing) notions of femininity. In reflecting, the protagonist recalls when

she’d started hearing her students say they were a size four or a size two, she thought surely that can’t be right. Even with anorexia. When they started saying they were trying to become a size zero, she laughed. What was next, a negative size? Yes! Agree to become invisible! Agree to actual female erasure! (16)

This introspective moment enables the reader to grasp how the protagonist’s former life experiences outside the facility parallel the epistemological and ontological frameworks she is being asked to embody and replicate inside the facility. Specifically, the dress functions as a metaphor for her subordination given its symbolization of female people being systematically trained to think of themselves as objects whose bodies must fit into clothing items in a manner which conveys conformance to strict aesthetic standards. The value of the female-object transposing herself into the clothing item is contingent upon the degree to which she conforms to the designated standard of beauty. Although the protagonist’s reflection stops here, the reader might extend it by noting that the patriarchal construct of normative femininity and its requirement that women conform to strict beauty standards functions in conjunction with another aspect of male domination: patriarchal scopophilia. I like to identify this ideology and praxis as the convergence of Laura Mulvey and John Berger’s discourses on the topic. In “Visual Pleasure in Narrative Cinema,” Mulvey recalls the historical definition of scopophilia: “the erotic basis for pleasure in looking at another person as object” (806). She goes on to argue that this visually dehumanizing form of objectification is a prevalent, normative mode of gazing in cinema such that female actresses are presented as passive spectacles to be looked at by male audiences. In his own configuration of patriarchal gazing, John Berger argues in Ways of Seeing that

One might simplify this by saying: men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only most relations between men and women but also the relation of women to themselves. The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed female. Thus she turns herself into an object-and most particularly an object of vision: a sight (47)

Here, Berger conveys the hierarchical nature of viewing under patriarchy. Men actively watch; women passively appear for the purpose of being watched by men. Additionally, and perhaps moreover, women also survey themselves through a male lens which is such because the male gaze involves looking at female people in ways that reduce them to objects. When women view their own selves in this objectifying way, their inundation in the system of male logic and praxis becomes evident such that, as once argued by theorist Julia Kristeva when interrogating female conditions under patriarchy in “The Transformative Feminine and Heterosexuality,” it becomes accurate to suggest that women don’t exist at all. The notion that women don’t exist at all becomes particularly germane to the concept of male viewing when the reader grasps Berger’s argument that, in a society predicated upon the organization of reality through a male lens, women disappear and also become men in the process of examining themselves. The dress that Jones is told to wear points towards these patriarchal principles by indicating that the objective of the facility is to cause her to conform to the androcentric edicts of society which insist that she perform a very parochial, patriarchal version of normative femininity which involves objectification and self-objectification (the latter form of objectification, self-objectification, transpires upon the donning of the dress because doing so is interpreted by patriarchy as a sign of one’s willingness to collude in her own oppression by adopting the visual logic prescribed by the system of male domination).

The persistent insistence of the patriarchy, exemplified through the demeanor of the counselor who encourages Jones to wear dresses, is recapitulated throughout the text. As the narrative continues to unfold within frameworks of devolution which involve the ongoing abrading of Jones’s independence and autonomy, she is forced to obtain a bikini wax. When she protests, the protagonist is told that she has no choice and is physically restrained (strapped to a table by male attendants) for the painful removal of body hair. As she continues to protest, Jones is told that she is operating in a childish manner. In response, Jones sputters “at the irrationality” (45) of the esthetician’s logic, with this somatic utterance pointing towards the fallacious nature of patriarchal rationale. Specifically, attempting to assert ownership over one’s own body is associated with adulthood, maturity, and self-respect. Conversely, children acquire an understanding of these principles as they grow older and have life experiences which teach them that they are entitled to various levels and dimensions of autonomy and independence irrespective of factors such as social position and economic standing. Yet the esthetician reduces Jones’s resistance to another individual claiming that her body can be misappropriated and misused to childishness because, given her collusion in the system of male domination which dictates that women have no bodily rights, her understanding of what constitutes querulous, immature behavior incorporates the idea that adult female people are “mature” enough to grasp that their bodies exist for patriarchal pleasure; this “maturity” is incompatible with resistance, and protests are thus associated with the childishness that results from one not understanding how the androcentric world operates.

True to life under male domination, the story worsens as time unfolds because, as the narrative progresses, Jones is increasingly subjected to the perverse, pernicious rules of male domination which are operative within the psychiatric facility. The unfolding of the text clearly conveys that the androcentric project is one predicated upon the denial of female personhood. This fact becomes evident at many points, including when facility representative Dr. Gagnon begins to conclude a meeting with her by stating “next week I’d like to discuss your diagnosis” (76). Jones responds “As would I” (76). The text notes that he looks at her after she gives this response and proceeds to ask “What, surprised she could handle such a grammatical construction?” (76). Here, the reader notes that Dr. Gagnon’s consternation is germane to the issue of identity. Specifically, in asserting that she would like to discuss something through the use of the self-referential term “I,” Jones asserts that she exists as an independent, autonomous being rather than operating as an ancillary, adjacent entity who belongs to a man. Dr. Gagnon’s surprise and ostensible resistance to this sequence of verbal self-assertion and certitude works to convey the patriarchy’s ongoing antagonism towards the concept and reality of axiological frameworks which include the valuation of female subjectivity. In a patriarchal planet where female subjectivity is a crime, the grammatical construction “I” is infinitely dangerous and damning.

In addition to providing readers with excellent commentary regarding the system of male domination, Tittle’s text offers individuals racial information which they can ponder in order to develop a more acute awareness of how racism, like sexism, operates as a discriminatory axiological framework predicated on a hierarchical structure in which one group dominates and dehumanizes another. In incorporating race into a discussion which had previously been confined to the domain of gender, Jones asserts “I recognize that my gender is important to other people….but I also recognize that although a lot of people, mostly white people, don’t identify themselves by skin colour–” (142). Her grammatical construction ends here with the agrestic em dash, but the reader’s cognitive processes regarding the signification of racial identification do not necessarily stop there. At the onset of the em dash, readers might find themselves pondering the issue of why white people choose to self-identify as white or not. This is an important issue for many reasons and has been discussed by numerous anti-racist scholars who seek deeper understanding regarding how whites can and do operate within the white supremacist structure. Whites choosing not to identify themselves by skin colour can function as a sign of white privilege insomuch as, while race is conferred upon black people as a marker of inferiority (given all the negative stereotypes attached to blackness) which they cannot avoid given the color of their skin, whites do not have to consciously and intentionally assert that they are white but can rather simply exist as fully human while being white (given that, according to racist logic, being white means being human while being non-white always represents the domain of the subhuman). In other words, whites don’t have to identify themselves by skin colour because they already are identified by white skin which represents positive stereotypes such as individuality, industriousness, moral purity, etc. This is part of white privilege. That Tittle chose to include reflections on whether whites choose to self-identify as white is important. This is the case because the references to race speak towards the aspect of radical feminist theory which, in critiquing the pernicious harms engendered by patriarchy, also subjects the edicts of white supremacy to scrutiny in order to facilitate deeper awareness regarding the deleterious impact that multiple systems of domination can have on individuals embedded in regimes of subjugation.

Readers who thrive on exposure to fictional texts which incorporate radical feminist theory into the processes of narratology, characterization, and plot development will likely love this text. Irrespective of the emotive and intellectual disposition one acquires towards the work, Gender Fraud will likely motivate the reader to reconsider her presuppositions regarding the sex/gender system and ponder how, within dystopic frameworks in which women who attempt to assert their independence and autonomy are accused of attempting to be male, patriarchy works to perpetuate its project of annihilating, or at least abrading, female subjectivity.